NetHack

The first roguelike I played was NetHack, one of the oldest and best of its breed. I played NetHack 3.1 in the fall of 1991, back when horses didn’t exist and”elf” was still a class.

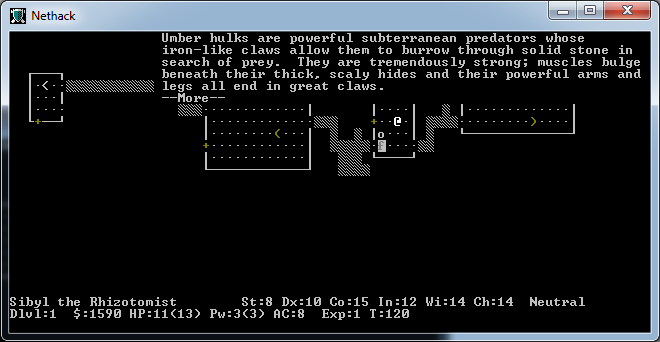

For the uninitiated, NetHack looks like this:

This is an ASCII representation of a dungeon. The @ sign is me, the + signs are closed doors, the o is a goblin, the f is my kitten, the brown parenthesis is a weapon of some kind – a crossbow, but I only know because I checked it earlier.

The only way to recognize things in-game (apart from walking up to them and seeing what happens) is to hit the slash key, which will allow you to move your cursor over things to find out what they are.

You can also type in random symbols to find out what they are in advance, and get a quick definition. This was amazing. I typed in every single letter of the alphabet, lower-case and capitalized, to discover umber hulks and leprechauns and quantum mechanics long before they showed up in my game.

But the NetHack manual and the in-game documentation won’t give you all the information you need. As a starting player, you don’t know about the dangers of drinking from fountains, the real purpose of candles, or why a purple h should terrify you.

And you die a lot. This is expected behavior.

You die a lot at first because you have no idea what you’re doing, and you die later because you do and yet it’s not enough. No matter how good you are, the goblin around the corner could still have a wand of death, and if it does, you’re probably toast.

NetHack is a ridiculously complicated game. You can learn its complications the hard way, or you can spend a lot of time with spoiler files. And no matter what bizarre thing you try (using a stethoscope on a statue; casting stone-to-flesh on a rock; enchanting a worm tooth), the dev team has gotten there first with a customized message and effect, because The Dev Team Thinks Of Everything.

NetHack is about surprise.

Many of those surprises are deadly. But you’re definitely surprised.

Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup

I tried Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup for the first time last week. Here’s a screenshot of a reasonably advanced game. (There’s an ASCII interface available, but I use tiles for most things that aren’t NetHack.)

Like NetHack, DCSS conforms fairly well to the Berlin Interpretation of “what is a roguelike”:

- random environment generation

- grid-based dungeon environment

- exploration, discovery, identification

- resource management

- turn-based movement

- permadeath

(among others)

In both games, you wander around collecting potions, scrolls, and wands. You fight monsters. You worship gods. You gain levels. You upgrade your gear. You get better at casting spells and swinging weapons.

But DCSS is an extraordinarily different experience from NetHack.

Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup is about strategy.

What’s the difference?

In NetHack, there’s a high chance of dying messily in the first few levels, especially if you’re not very familiar with the game. DCSS operates the same way.

But in NetHack, your chance of unfair death remains constant throughout the game. You can drop a bridge on your head, or irritate your god into smiting you, or choke to death on meatballs, or stone yourself by sacrificing a cockatrice barehanded. Many of these can be avoided – but you have to know they’re there to avoid them.

This is not the case in DCSS, where your control over the game and the character increases as you move deeper into the dungeon. With rare exceptions (initial item scrambling, for example), DCSS routinely provides all necessary information for the player to make a meaningful decision.

To illustrate:

Eating corpses (with consequences) in Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup

In DCSS, you can carve up dead beasts for “a chunk of flesh”, and eating these chunks of flesh is a standard way to gain nutrition. But if you kill and carve up a sky beast in DCSS, you will then have “a chunk of mutagenic flesh”. If you know that mutations exist in DCSS (which you almost certainly do, by the time you meet a sky beast), then you can reasonably deduce that eating a mutagenic chunk of flesh will give you a mutation. DCSS goes out of its way to give you helpful information.

Eating corpses (with consequences) in NetHack

NetHack doesn’t have mutations per se, but the effects of eating corpses vary widely. The closest NetHack gets to warning you about this is with the relatively cryptic message, “You are what you eat”, which occasionally shows up in fortune cookies*. This is a decent guideline for winter wolves (which grant cold resistance), but not for floating eyes (which grant telepathy).

NetHack: When you eat something and get an unusual effect, it’s an exciting surprise (possibly not in a good way).

DCSS: If you eat something and get an unusual effect, you knew exactly what you were getting into and brought it on yourself.

Neither of these is wrong – but they are different, and they will appeal to different kinds of players. The things that Ryan Baudoin loves about NetHack are the exact things that John Brownlee complains about (it’s a general roguelike article, but scroll down to the DCSS section.)

Personally, I prefer NetHack to Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup. Admittedly, DCSS has had less time to earn my love – but NetHack is perhaps my favorite game ever. Even now, it can still present me with surprising new situations, and I doubt I’ll ever feel as if I’ve encountered (let alone mastered!) everything in the game.

Design goals

The DCSS team explained their design philosophy in detail. They knew exactly what they wanted –

- Major design goals

- challenging and random gameplay, with skill making a real difference

- meaningful decisions (no no-brainers)

- avoidance of grinding (no scumming)

- gameplay supporting painless interface and newbie support

- Minor design goals

- clarity (playability without need for spoilers)

- internal consistency

- replayability (using branches, species, playing styles and gods)

- proper use of out of depth monsters

Everything in DCSS is shaped with these design goals in mind. Many games iterate on new features in new versions, but the DCSS team routinely removes old features that didn’t prove out, thus ensuring that the game remains coherent to their vision. By having this kind of focus, the team ensures that DCSS will remain appealing to its core audience.

The NetHack dev team is notoriously closemouthed**, and they’ve never released a public design document***, but it’s clear that NetHack’s high-surprise/high-risk experience is deliberate. (If not, they’ve made bad design decisions for 28 years or so, which seems pretty unlikely.)

NetHack and DCSS are both exceptional, but smashing the two together wouldn’t create a better game. Each game is tuned to a different set of design goals, and those goals contradict one another.

That’s why it’s worth knowing your design goals from the outset. When you’re making a game, it can be tempting to pile every feature you’ve ever heard of into the design plan. But you don’t need every feature, and no one game can support them all. It’s better to plan for a specific experience and get it right.

* The chances of getting it are worse than 1 in 700. And to top everything off, fortune cookies often contain false rumors, or dangerously misleading one. Consider “Eat 10 cloves of garlic and keep all humans at a two-square distance.” There is a use for eating garlic, but this isn’t it.↩

** “Notoriously closemouthed” = “People keep thinking they’ve dropped off the planet”. It’s always a surprise to discover they’re still around and actively working on the next version.↩

***Alex Smith wrote a design philosophy document for NetHack4 [http://nethack4.org/philosophy.html], which is fairly insightful, but he’s not part of the dev team. Despite the title, NetHack4 is a fan-made offshoot, comparable to SLASH’EM.↩

Thank you to everyone supporting Sibyl Moon through Patreon!

If this post was interesting or thought-provoking, please consider becoming a patron.