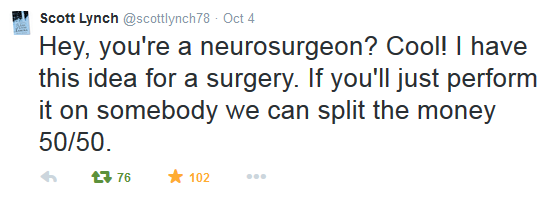

Someday, every successful novelist gets an offer that goes like this:

“I have this great idea for a book! If you write it, I’ll share the profits with you!”

It’s not very helpful.

I bet every successful game dev studio gets the same offer, and the problem with that offer is that ideas are worthless. The value’s not in the idea, but in the execution.

That’s why I didn’t get too worried when I described an upcoming paper prototype to a friend and, after listening carefully, he said, “You know, that sounds like Pathfinder ACG.”

I said, “Oh! Really? I’ve never played Pathfinder ACG.”

We were heading to a board game night where the host happened to have Pathfinder ACG, so we pulled it out and convinced two more people that they wanted to play. I was relieved to realize that it wasn’t, in fact, all that much like my game.

…but what if it had been?

It’s dismaying when your idea overlaps someone else’s. When Caelyn Sandel and I released our debut text adventure One Eye Open, reviewers reliably compared it to Ian Finley’s Babel – but we had never played Babel. (Our big inspirations were the Silent Hill series and Storm Cellar, an incomplete IF horror game by Paul Scheckarski.)

But here’s the thing: the magic isn’t in the idea.

Consider the Food Network show Chopped. It’s a cooking competition, and each round begins when the chefs open up their mystery baskets and peer down at a set of mystery ingredients. Sometimes those ingredients are pretty mundane, like tofu or watermelon or flank steak. Sometimes they’re completely off the wall, like olive loaf or hamantashen or dragonfruit. The chefs have to use all the ingredients in a balanced, composed dish before the clock runs out, and time starts… now.

All of the chefs start from the same place. In addition to the mystery ingredients, they have access to a group pantry and a group fridge. But they can’t call in an order of fresh lobster or whip black truffles out of their back pockets. And that clock is ticking relentlessly down.

Despite these limitations, they make wildly different dishes. Given the same four ingredients, one contestant makes a soup, one makes salad, one makes tacos, and one makes fritters. Or they all make salad – but they make different salads, different enough that the judges can try them and tell them apart and judge them meaningfully.

The Chopped concept might sound familiar, if it’s properly reskinned….

Here’s the theme. Make a game. You have 48 hours.

The yearly Global Game Jam is a similar event in the world of game design. Every participant starts with whatever tools and techniques they can bring to the table. Every participant attempts to make a game in 48 hours based on a theme revealed at the start of the event.

A theme isn’t quite the same as an idea. But it’s still a starting point – and once you have that starting point, the measure of your success stems not from that starting point, but from what you do with it.

Over the course of creating a game, there are a thousand decisions to make that stretch far beyond the initial idea. It’s not that initial idea that makes or breaks the game, but the thousand decisions that follow it.

For example:

Take the idea “dance video game”. There are at least three major executions of that idea so far, each with a distinctly different flavor.

Dance Dance Revolution – In essence, Dance Dance Revolution is a rhythm game about pressing buttons at the right time. Because the buttons are four squares on a dance pad, the players press them with their feet. Instructions are delivered via a stream of moving arrow cues. The experience focuses on precision rather than form.

Just Dance – Just Dance was created as a party dance game that anyone could pick up and play. Like DDR, Just Dance harnessed only one part of the body for dance detection – in this case, one hand, since it originally used Wii technology to track dancers’ movements. (Later versions have harnessed Kinect technology.) Instructions are given in shorthand with icons, and in more detail by providing a neon dancer whose movements players can imitate. Moves are graded on a scale rather than a binary hit-or-miss.

Dance Central – Harmonix’s goal was to provide the most authentic video game dance experience available, with dances authored by professional choreographers rather than designers, teaching moves that people could use in a real dance club. Dance Central was the first to use the Kinect technology for whole-body tracking. The instruction method and grading are similar to Just Dance’s, although the visuals are extremely different. Because of Dance Central’s focus on real choreography and because of full-body tracking, the game is less pick-up-and-play than Just Dance.

What distinguishes these games from one another? The user interface. The core tracking technology. The way instructions are conveyed to the player. The visual design. The scoring system and metrics. The sound design. The songs available. The choreography. The list goes on. This is the execution – and it’s worth a lot more than the idea “dance video game”.

Ideas are cheap. But the execution… that’s where the magic is.