The first time I participated in a game jam was the 2012 Global Game Jam, and I impressed Courtney Stanton. She asked me afterward:

“How were you planning to finish that in a weekend? If you had a month, maybe… but 48 hours?”

Once I got over being A Special Kind of Impressive, I learned an important lesson about scope.

What’s scope?

In the context of game development, “scope” refers to the projected size and complexity of a game project.

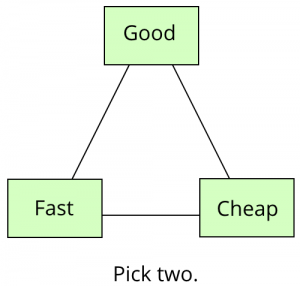

You’ve likely seen this diagram before, or one like it. (Probably not this one, since I whipped it up a few minutes ago as part of this post.) This diagram is applicable to any project, but it can function specifically as a description of scope in game dev.

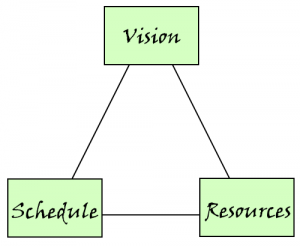

Of course, it’s a simplification. Rather than a simple “pick two”, you balance among the three. A better version for game dev is this one:

In a large game dev project, the producer is in charge of keeping an eye on the scope of the game. What’s the vision for the project (aka, what do we want to make?) What resources do we have? How fast can we create that vision with those resources? (Is it even possible?)

Schedule ↓ : resources ↑ or vision ↓

Resources ↓ : schedule ↑ or vision ↓

Vision ↑ : resources ↑ or schedule ↑

That’s why the producer is also responsible for reining in scope creep.

Scope creep

It creeps… It crawls…

Scope creep happens when features get added to a project after the initial time and budget estimates are done, especially when those features are added in an uncontrolled, undocumented way. It’s extremely easy for this to happen, especially in games, where it’s often hard to tell what will be fun, interesting, or necessary until the project is well underway.

One of a producer’s most important jobs is to protect the devs from scope changes, both those coming from outside the team (“I think we need a miniboss on this level”) and those coming from inside the team (“I know I said this system was done, but it will be so much easier to work with later if I refactor the code now!”) Learning to say no is an important skill.

That isn’t to say a producer’s job is to say no all the time. That code refactor might save months down the line, and that miniboss might be the best thing that goes into the game – but every feature change costs time and requires personnel. Instead, a producer’s job is to make sure the changes have a good reason and that the cost of those changes is understood and approved before anyone starts working on those changes.

Back to the game jam

In a game jam, you likely don’t have a formal producer, and you almost certainly won’t have someone dedicated to the role. In order to get this right, you’ve got to get it right from the beginning – despite having all the same uncertainties about tools, personnel, and “will this be fun?” that a giant studio and a giant game project have.

The good news is, you have all the pieces of the puzzle available.

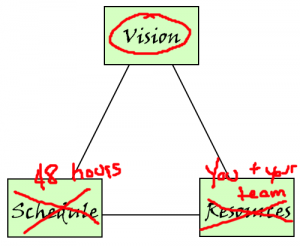

You know your resources. Your budget is nothing (unless you’re way more enthusiastic about game jams than I am.) You have yourself, you have the rest of your team (maybe 2-3 people), and you have whatever skills and software your team already owns (or can beg or borrow for the time being.)

You know how much time you have. You have 48 hours, minus whatever time you need for eating, sleeping, showering (important), and not going mad.

Take a good look at that…

To scope for a game jam, the question is:

What can you make in that period of time, with those resources, with that budget, that is a viable game?

Make that game.

Step 1: Start with a plan

At the top of the jam, plan your project out in advance, and look specifically at the minimum viable product.

– What is the simplest, smallest form of your game concept?

– What is the minimum execution of your game mechanic?

– What is the minimum amount of design work you need?

– What is the minimum amount of art you need?

– What is the minimum amount of sound you need?

Once you have those estimates, ask yourself: is this feasible in 48 hours, with this team, without any external resources?

If the answer is “yes”, you have a good game jam project. Go for it!

If the answer is “no”, then your game jam project is too big. That’s unfortunate, but you’re better off realizing that immediately, while you still have time to change your mind, instead of 48 hours down the line, when you are sad.

Step 2: Execute that plan

Many game jam teams don’t produce a finished game. If you produce a finished game – something a player can start and finish, with gameplay in the middle – then you’re ahead of the curve.

If your plan is correctly scoped, and you take that plan and successfully execute it to the minimum, then you have created a game. Hooray! At that point, you can add whatever features you want without endangering the project as a whole.

You will be tempted to expand your feature list before you finish that minimum execution. Don’t succumb to this temptation. It might not look like you need the time – but it’s amazing what can go wrong along the way. I’ve been doing digital game jams for years, and there have been major bumps along the road in every single one, with reasons ranging from “None of the programmers are running the same OS” to “Can’t art, unrelated drama is destroying my brain” to “What do you mean, ‘version control’?”

Once you get the minimum execution done, then you can add features on top of your minimum without any risk of failing to complete a game. And that’s fantastic! Consider it a cookie for your hard work.

When I participated in iamagamer.ca, our team was really well-behaved about sticking to the plan. We got our minimum done by Saturday evening, and I got really excited because it looked like we were going to have time to implement a fourth enemy type.

Our artist Caelyn did all the work… but there just wasn’t enough time for me and Ethan to get the lizards implemented mechanically. The lizards languished tragically in the folder where unimplemented lizards must go.

It happens. It’s a game jam. We released Trapper’s Trials and moved on.

The most important thing about game jams

If your game jam project doesn’t work out, that’s okay! Game jams are 48 hour projects, and at the end of those 48 hours, you can wipe the slate clean. Game jams are educational and good for networking and good for skill-building, and they give you opportunities to try new and different things – but at the end of the day, they’re primarily for fun.

Which pretty much means:

How to win at game jams: 1. Go 2. Make a thing it doesn’t have to be good or finished 3. Ok cool you won @BooDooPerson @antumbral

— Khaleesi of SJWs (@TheQuinnspiracy) October 27, 2014

Yay game jams!